For the Moravian memoirs the use of the Voyant Tools helps understand more of the idea or the theme of a particular text more easily in one website. In analyzing the text that was given my group has come up with a research question, “How did Esther Latrobe’s relationship with God affect her lifestyle, and help her recover from such illnesses and hardships? ” There is also a question that I propose and it is, ” Would her values of life be any different if she was put into this time period?” These tools may help us find the answer we need. However, as Whitley points out “visualizations are intended neither to stand as definitive interpretations of literary text nor to provide direct answers to research question.”(187)

When looking at the tools that are given it seem that these tools would help us understand more on these research questions. The reason is that many of the traditional tools are usually pen and paper that has only one copy of existence. But in the Digital age that we live, a person is able to access things more quicker and understand the connections of the terms and their usage in that text better and faster. We are able to compare and contrast between text better in finding the differences and “digital technology (help us) search for patterns and trace broad outlines.” (188)

When looking at the tools that are given it seem that these tools would help us understand more on these research questions. The reason is that many of the traditional tools are usually pen and paper that has only one copy of existence. But in the Digital age that we live, a person is able to access things more quicker and understand the connections of the terms and their usage in that text better and faster. We are able to compare and contrast between text better in finding the differences and “digital technology (help us) search for patterns and trace broad outlines.” (188)

While using the Voyant tool it has showed the connections of the theme that was around the terms that were commonly used. The key terms that were most frequent in the letters were the Samuel text was lord, time, heart and death. These terms came from the other group that we shared with. By using the cirrus tool it allowed us to visualize the top frequent words in a word cloud. That shows a pattern of religion being the main center of it all. In the Latrobes letters it was about a women who has lived life of misery and sickness in her life, yet having a positive attitude towards her life and to others. Knowing that one day her God will give her a better life after death. With the cirrus tool and mandala tool it allowed me to distinguish the key terms of the Letters in a bigger picture. With key terms being lord, saviuor, dear, god and heart it conveys that most of these texts convey a message that a person life revolves on the teachings of Christianity and what keeps that person living as a good person. There are collocates in this text like, “Dear Saviour let me take my soul at the foot of thy cross,for ever having my eyes fixed on thy sacred body, bearing my sins’ heavy load.”(pg 6) with the Dear and Saviour being next to each other. For example, with the tool of Corpus Collocates it describes the patterns and amount of times that terms collocate with each other. Being that the most collocate terms that go together are Dear, Saviour and Death. Even though Death is not much of a prevalent word in the Latrobe article. It did have a prevalent theme around it while also giving the same prevalent theme of religion being the main factor of her life. With the Lord being the most frequent term for both text, it describes her wanting advise from God to help her find peace in her life and those around her. One thing to note is that in this letter is that it had more of a emotional story of a person than describing the whole environment.

In the end, the key terms and the patterns that were shown by the tools give us an understanding of their world and life. It lets us see the prevalent themes of the past that may be common for them, but uncommon for us. As Whitley would explain it, “visualizations help us perceive patterns in data that we might otherwise miss” (187) in order understand the stories of our past.

Mauricio Enrique Martínez is a student who is majoring in Cultural Anthropology and Japanese at Bucknell University. A wanderer in life.

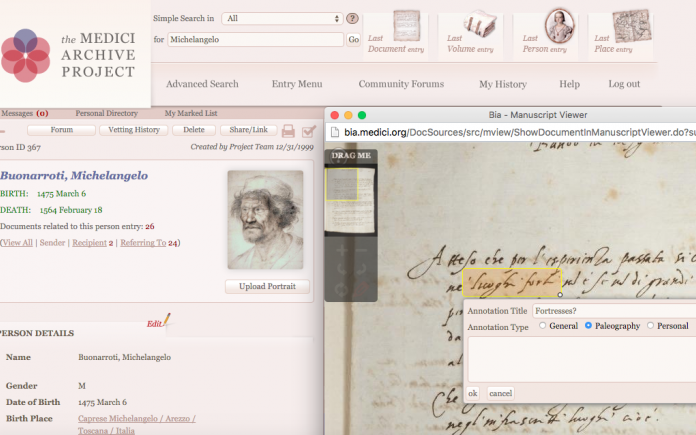

. Specifically, when an archival document can be accessed digitally, it takes away from the special experience of traveling to the archive and handling the actual document. When a document is digitized, the document is often static, presented as a photograph or transcription. This presentation could potentially make a researcher miss an important aspect of the document, such as something that is written more lightly, that they would have been privy to if they were in the presence of the actual document.

. Specifically, when an archival document can be accessed digitally, it takes away from the special experience of traveling to the archive and handling the actual document. When a document is digitized, the document is often static, presented as a photograph or transcription. This presentation could potentially make a researcher miss an important aspect of the document, such as something that is written more lightly, that they would have been privy to if they were in the presence of the actual document. that are studying a similar topic. Physical archives also offer the “wide-angle perspective” (185) that Whitley spoke about. However digital archives offer a different experience. As Whitley writes, “In browse mode, digital archives allow for a wide-angle perspective on their material by trusting to the wanderings of a curious mouse clicker. In search mode, the hope is that a search engine will serendipitously discover information that a browsing scholar or student might otherwise miss” (186). I would not say that the digital archive is better than the physical archive and vice versa, just that the two offer very different experiences. In my opinion, a combination of both may be the best approach for a browsing scholar or student.

that are studying a similar topic. Physical archives also offer the “wide-angle perspective” (185) that Whitley spoke about. However digital archives offer a different experience. As Whitley writes, “In browse mode, digital archives allow for a wide-angle perspective on their material by trusting to the wanderings of a curious mouse clicker. In search mode, the hope is that a search engine will serendipitously discover information that a browsing scholar or student might otherwise miss” (186). I would not say that the digital archive is better than the physical archive and vice versa, just that the two offer very different experiences. In my opinion, a combination of both may be the best approach for a browsing scholar or student.