While transcribing my assigned memoir, I paid close attention to every individual word, rather than looking at the document as a whole. However, after my transcription was complete, I was able to read over the document and really pay attention to the actual story of Joesph Lingard’s life. My memoir is mainly about Joesph Lingard and his family and how he found his way into the congregation. The memoir discusses how Joesph and his wife were extremely unhappy and joined the congregation to rid themselves of this unhappiness. At first, Joesph and his family did not have a home near the congregation, so the brethren actually offered his family a place to stay until they found something more permanent. The memoir continues on following Joesph through all steps of his journey into joining the congregation. In the end, Joesph falls ill. As we move forward, I am excited to look more into not only Joesph but his family members, specifically his son, because they were so important in the memoir.\

Edward Whitley writes, “the virtue of information visualization is that it can make complex data sets more accessible than they otherwise might be” (188). Whitely is correct in that information visualization tools, such as Voyant, make complex text, like the Moravian memoirs, much more digestible than they might seem at first. Our group research question is: Was the congregation perceived in a positive or negative way in the lives of Moravian People? This approach has been somewhat helpful in answering our research question, but it certainly doesn’t offer a complete answer. This approach has been helpful in getting a better sense of how the Moravian people viewed the congregation because we have been able to pinpoint where the word congregation has been used and the words surrounding it, as I talk about below.

Using Voyant has allowed me to interact with my assigned memoirs in a new way. TextualArc allowed me to see the flow of  keywords throughout my document in a neat visual. This tool painted out a nice overview of the text, and “creat[ed] visual abstractions of textual patterns” (193), which I used before diving into other tools that gave more detailed data. In a way, I used this tool to see a summary of my document. In my opinion, the most helpful tools on Voyant are those that allow you to see the frequency of different words in the text. Both the Cirrus word cloud and Document Terms allowed to see the frequently used terms in two very different, but equally helpful, ways. First, the

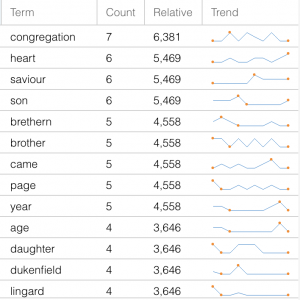

keywords throughout my document in a neat visual. This tool painted out a nice overview of the text, and “creat[ed] visual abstractions of textual patterns” (193), which I used before diving into other tools that gave more detailed data. In a way, I used this tool to see a summary of my document. In my opinion, the most helpful tools on Voyant are those that allow you to see the frequency of different words in the text. Both the Cirrus word cloud and Document Terms allowed to see the frequently used terms in two very different, but equally helpful, ways. First, the  word cloud emphasizes a frequently used to term by making it larger. Observing my word cloud, I was able to see that congregation, heart, saviour, son, and brethren were most frequently used. I did not find any collocates to be particularly useful because no words were associated with another more than once, so no phrases presented themselves as frequently used in the document. These words allowed me to see that Joesph Lingard’s story of how he joined congregation was more instrumental to the text than I originally thought. However, the Document Terms gives the quantitative data to see how many times each of those words were actually used in the specific document, but not the whole corpus. For

word cloud emphasizes a frequently used to term by making it larger. Observing my word cloud, I was able to see that congregation, heart, saviour, son, and brethren were most frequently used. I did not find any collocates to be particularly useful because no words were associated with another more than once, so no phrases presented themselves as frequently used in the document. These words allowed me to see that Joesph Lingard’s story of how he joined congregation was more instrumental to the text than I originally thought. However, the Document Terms gives the quantitative data to see how many times each of those words were actually used in the specific document, but not the whole corpus. For  example, Document Terms showed that heart was used 18 times throughout the text and showed a trend line. This trend line is an especially helpful visualization tool in that is shows me where in the text the word is used most frequently, which allows me to ask more questions about that particular section of the document. For example, where the word heart is most frequently used, Joesph was speaking about his journey to join the congregation and how the brethren offered him lodging. Joseph’s frequent usage of “heart” shows that these kind actions deeply affected him. Overall, These tools are helpful because “amid the chaos of more frequent repetitions,” the tools allow me to see patterns that I “may have missed with close reading” (191).

example, Document Terms showed that heart was used 18 times throughout the text and showed a trend line. This trend line is an especially helpful visualization tool in that is shows me where in the text the word is used most frequently, which allows me to ask more questions about that particular section of the document. For example, where the word heart is most frequently used, Joesph was speaking about his journey to join the congregation and how the brethren offered him lodging. Joseph’s frequent usage of “heart” shows that these kind actions deeply affected him. Overall, These tools are helpful because “amid the chaos of more frequent repetitions,” the tools allow me to see patterns that I “may have missed with close reading” (191).

Samantha is currently a sophomore Markets, Innovation, and Design major in the Freeman College of Management at Bucknell University in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. At Bucknell, Samantha works as a Student Development Officer for the Student Calling Program and is a member of Alpha Lambda Delta Honor Society, Women in Finance, and is treasurer for the Chi Mu Chapter of Chi Omega Sorority. She graduated from the Morristown-Beard School in Morristown, New Jersey in June 2017. Samantha resides in Harding, New Jersey and during the summer, Samantha works at Basking Ridge Country Club.

. Specifically, when an archival document can be accessed digitally, it takes away from the special experience of traveling to the archive and handling the actual document. When a document is digitized, the document is often static, presented as a photograph or transcription. This presentation could potentially make a researcher miss an important aspect of the document, such as something that is written more lightly, that they would have been privy to if they were in the presence of the actual document.

. Specifically, when an archival document can be accessed digitally, it takes away from the special experience of traveling to the archive and handling the actual document. When a document is digitized, the document is often static, presented as a photograph or transcription. This presentation could potentially make a researcher miss an important aspect of the document, such as something that is written more lightly, that they would have been privy to if they were in the presence of the actual document. that are studying a similar topic. Physical archives also offer the “wide-angle perspective” (185) that Whitley spoke about. However digital archives offer a different experience. As Whitley writes, “In browse mode, digital archives allow for a wide-angle perspective on their material by trusting to the wanderings of a curious mouse clicker. In search mode, the hope is that a search engine will serendipitously discover information that a browsing scholar or student might otherwise miss” (186). I would not say that the digital archive is better than the physical archive and vice versa, just that the two offer very different experiences. In my opinion, a combination of both may be the best approach for a browsing scholar or student.

that are studying a similar topic. Physical archives also offer the “wide-angle perspective” (185) that Whitley spoke about. However digital archives offer a different experience. As Whitley writes, “In browse mode, digital archives allow for a wide-angle perspective on their material by trusting to the wanderings of a curious mouse clicker. In search mode, the hope is that a search engine will serendipitously discover information that a browsing scholar or student might otherwise miss” (186). I would not say that the digital archive is better than the physical archive and vice versa, just that the two offer very different experiences. In my opinion, a combination of both may be the best approach for a browsing scholar or student. Bentham invites the public, specifically anyone interested, to access and transcribe Bentham’s work. The project doesn’t have a sole contributor, but rather many. This method allows for more transcriptions to become available in a shorter amount of time, simply because so many people are able to

Bentham invites the public, specifically anyone interested, to access and transcribe Bentham’s work. The project doesn’t have a sole contributor, but rather many. This method allows for more transcriptions to become available in a shorter amount of time, simply because so many people are able to  put on a platform for others to access. In this way, a once single non-digital copy of Bentham’s work becomes available for people to access infinitely digitally. This project seems to be very similar to our work with the Moravian Lives project in the way that we both will be transcribing manuscripts for others to access.

put on a platform for others to access. In this way, a once single non-digital copy of Bentham’s work becomes available for people to access infinitely digitally. This project seems to be very similar to our work with the Moravian Lives project in the way that we both will be transcribing manuscripts for others to access. assembles them in a way that onlookers are able to see patterns between the images. Selfiecity uses “imageplots” which places the selfies on top of each other so that they oriented the same way. In the case of Selfiecity, the medium of the subject

assembles them in a way that onlookers are able to see patterns between the images. Selfiecity uses “imageplots” which places the selfies on top of each other so that they oriented the same way. In the case of Selfiecity, the medium of the subject matter largely determined the way in which the data was represented digitally. Selfiecity’s data was made up of images, so using a visualization approach was an obvious choice. Using visualization allowed Selfiecity to establish patterns between the selfies more easily and made their findings more apparent to others.

matter largely determined the way in which the data was represented digitally. Selfiecity’s data was made up of images, so using a visualization approach was an obvious choice. Using visualization allowed Selfiecity to establish patterns between the selfies more easily and made their findings more apparent to others.