Memoir Summary:

Elizabeth Grundy’s memoir is an account of her life, (February 6, 1717 – May 9, 1799) which she dictated to her son. She starts out by talking about her childhood, as far back as she can remember. Her parents were very strict, and were of the Presbyterians persuasion. Elizabeth was the youngest of her sisters, and had no brothers. Her father died when she was twelve which left her mother to care for them alone. Elizabeth became much more involved in religion around this time and practiced it regularly throughout her teenage life. When she was twenty two years old, she started school keeping. Shortly after this she met her husband, who was a member of the church of England, and they had a son together. On February 22, 1748, when her husband was only twenty nine years old, he died. Elizabeth, much like her mother, was now a widow and had to care for her baby son, in the middle of her second pregnancy. She explained how she managed to handle this, by turning to God when she felt overwhelmed, and making sure her children worshipped God to reap his benefits. Her oldest son William died after a long illness when he was seven years old. In 1756, she moved to Dukenfield as a member of the Brethren church, where she eventually started up a school for girls. About ten years later when her youngest son was old enough to live on his own, he left Dukenfield for Fulneck, where he eventually would get married and be asked to start a school for the Brethren society. Elizabeth Grundy also had a daughter, who after her first delivery passed away, and the child died with her. After this she went to live with her son in 1787, and began a school for girls where she lived out the rest of her days worshipping her Savior.

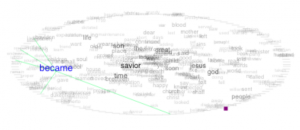

The full compiled transcription that I entered into Voyant is one document that consists of 4,979 total words, and 1,314 unique word forms. The vocabulary density of my group’s document is 0.264, and the average words per sentence in this document is 28.6 words. The five most frequent words in the corpus are savior, time, god, son, and jesus. Savior almost always comes after “our”, and contains either the words god, jesus, or christ before or after it is used. Time usually comes right after a set of words such as “about this”, “at this”, “at any”. God is used mostly around the word “people”. Son almost always comes after the words “her” and “my”, and occasionally “the”. Jesus is often surrounded by the words Christ, Lord, and Savior in this document.

The research question my group and I are investigating is, how does the frequency of key terms change throughout the document?

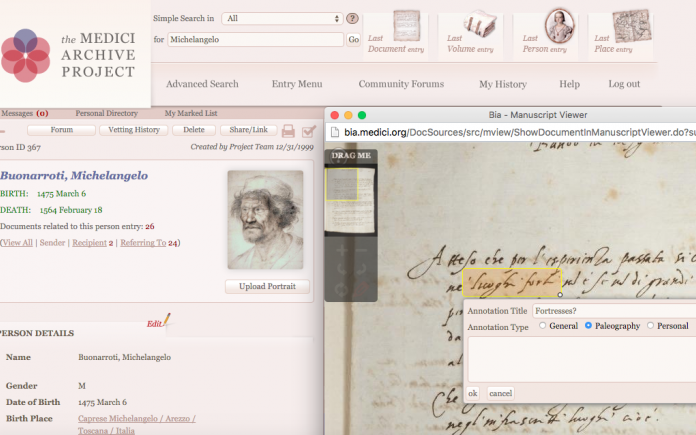

The first tool I used to visualize my text is called TextualArc. I chose to start with this one because it was mentioned in Whitley’s article, and I wanted to figure out what its purpose was. The creator of this tool W. Bradford Paley, wrote that he wants “to help people discover patterns and concepts in any text by leveraging a powerful, underused resource: human visual processing”(Whitley, 197). This tool is interactive and as you hover your cursor over all the different words in the ellipse, lines will pop up connecting to its collocates. This ellipse contains every word that is used in the document, and the cloud in the center of the ellipse is a color coated array of the text’s most frequently used words. The words in the middle are used commonly throughout the entire document, while the words on the boundaries of the ellipse are specific to certain segments of the document.

TextualArc is helpful in figuring out which terms in the document are used the most frequently, and throughout the entire text. Without a tool like this, it would be a very long process to figure out the most frequently used terms, and what their collocates are. Which is exactly what Whitley was referring to when he said “the virtue of information visualization is that it can make complex data sets more accessible than they otherwise might be”(Whitley, 188).

Word clouds have proven to be quite popular with internet users, both for their playful aesthetic quality and for their practical ability to visually identify the patterns of meaning in large and potentially unwieldy texts”(Whitley, 198). I like word clouds because of how simple but effective they are. These to me are basically condensed summaries of texts. Instead of writing out a couple paragraphs to explain what happened in a text, you can just look at the most frequently used terms organized randomly, and be able to gain a little bit of insight to what the text was about. Obviously you won’t be able to actually understand any of the details that go on in a text, but it will give you a decent overview of what the text is about.

This graph uses trends to visualize how often the most frequently used terms appear throughout the document. According to the data, the word savior was the most used term in the first two segments of the document, as well as the fifth, sixth, and eighth. Son was the most used word in the third and the tenth segments. God is the most used word in the fourth segment. Time is the most used word in the seventh and ninth segments of the document. This graph directly shows us how the key terms change over the course of the text my group and I created. This answers our research question because its shows us that although savior is the most frequently used word in the document, it is not the most frequently used word in each segment of the document, or throughout the document. It actually changes throughout the document, but the overall highest used word savior. If I was going to try and figure out all of the data by myself without the use of technology, it would mean counting by hand the 4,979 words in the document, and figuring out how many times every word is repeated if it is. It would be extremely tedious and difficult. These tools allow us to create helpful visualizations out of texts very efficiently, and they show us a lot about the relationships between different types words and their frequencies.

Caleb Broughton is an Econ major who plays on the baseball team at Bucknell University. Born in Lebanon, NH on November 6, 1998.